Summary

- There are two possible approaches to equalising constituencies: providing equal access to representation, and providing equality during an election.

- The first suggests equalising constituents (which includes non-voting residents), the second involves equalising registered or potential voters.

- Historically there was not much difference between these two groups. Increases over the last few decades in the population ineligible to vote mean that these different principles are now likely to lead to different results.

- Equalising on registered voters shifts results slightly in favour of the Conservative party, while equalises on population shifts results slightly in favour of the Labour party.

- Arguments made by political parties are reflective of their position in the system. The principles they see as important tend to be those that justify their current power, or that critique their current lack of it.

- Arguments for equality of access to representation depend on the idea that an MP represents all their constituents. But the presence of non-voters changes the political result without their input. Representation without participation cannot reliably be to an individual or a group's benefit.

- Arguments for equality during an election require going beyond equal boundaries to reforms that deliver proportional results. The same objections to representation without participation applies if participation isn't meaningful.

- In both cases the problem results from a lack of political representation (people having the representative they would choose to represent them) rather a lack of numeric representation.

- Extending voting rights to all residents resolves the rift between the population and the electorate, and smooths over several practical issues of representation.

Heading Image: George Pagan III on Unsplash

Introduction

The 2019 Conservative Party manifesto included a promise to equalise parliamentary constituencies. In practice, this means following the equalisation rules in the (never fully implemented) Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act 2011 but without the requirement to reduce the number of constituencies from 650 to 600. The wording in the manifesto is:

We will ensure we have updated and equal Parliamentary boundaries, making sure that every vote counts the same – a cornerstone of democracy.

The importance of equality is a long-standing part of the boundary debate. In the debate of the 1944 bill which set up the modern system of reapportionment, Herbert Morrison described the key principle as being that:

[S]o far as it is practicable each Member ought to represent an equal number of constituents.

This and the modern manifesto are similar sentiments but there is a key difference: one talks of equality of votes, and the other of constituents. Within the idea of equalising constituencies there are several numbers that can be equalised, and this in part depends on what the goal of the exercise is. Is it to give people an equal share of a representative? Or give voters an equal share of the election?

Currently the process of equalising constituencies is based around the number of people registered to vote. My position is that this is an accident of history rather than a deliberate choice. When there was a wide gulf between the electorate and the population in the early twentieth century, the constituencies were equalised on the overall population. The conceptual and practical difference between the two closed with the extension of the franchise to almost all of the population, and only re-opened with significant migration from non-Commonwealth countries in the 21st century. In between those times, there is little sense in arguments about voting rights that the population and electorate were seen as substantially different groups of people. It is in this middle period where the modern system of reapportionment was created, and so the democratic problem of resident non-voters is not addressed.

The increased number of resident non-voters means different approaches result in political differences in election results. Stricter division based on the registered electorate favours the Conservative party, while division based on population favours the Labour party.

The stated goal of reform is to make voters more equal, but the most visible political argument is about relative unfairness between the two largest parties. As both parties tend to be overrepresented compared to the number of votes they receive, the overall effects of these arguments over apportionment are small in comparison to the reallocation of seats that would follow a change of the voting system

That debates about boundaries are a sideshow to the argument about proportional representation has been appreciated from the beginning of the modern system in the 1940s. One response to this has been an argument that the concern is misplaced because MPs represent all constituents, including those of other parties and non-voters. This is an argument that the election is of less importance than representation. It implies that equalisation based on population (rather than electorate) would be a better approach, as this gives every person an equal share of their MP.

The logical results of these two positions (equal voters vs equal representatives), if taken seriously, should lead their advocates to different policies than they currently hold. That this does not happen reflects that parties are concerned with political equality only as much as it is compatible with their primary belief that they should hold power. My goal is to untangle some of the overlapping arguments about equality and representation, and give a clearer way of thinking about the choices available.

How to equalise

There are (at least) three different options when ‘equalising' constituency boundaries. You can aim for equal numbers of:

- Registered voters

- Eligible voters (citizens)

- Population (residents)

Currently the Boundary Commissions in the UK are tasked with equalising the number of electors in each constituency (option A). This is the number of people who are registered to vote on the electoral rolls at the time of the reapportionment rather than the number of people entitled to be on the electoral rolls (option B).

Internationally, some countries operate on another principle and aim for an equal number of people (vote eligible or not) in different constituencies (option C). In the US and Canada seats are assigned based on population. In Australia, seats are divided among the states based on population, but then apportioned within states based on electors. These differences tend to result from the political and demographic situation that existed when rules were formed, rather than direct decisions on the underlying principle.

Population vs electorate

Expansions of the franchise and changing ideas of accuracy led to changes in which concepts were important to equalisation. In the UK, most of the early language around apportionment in the late 19th century was based around population rather than electors. The 1885 instructions to the Boundary Commission for England and Wales talked of population:

In dealing both with County and Borough divisions, the boundaries of the divisions must be adjusted so that the population, excluding in the case of County division that of the Parliamentary Boroughs, may be proximately equalised and in the arrangements of the divisions special regard shall be had to the pursuits of the population.1

The 1917 redistribution was similarly based on a mid-year estimate of population.2 The switch to electorate based language can first be seen in a 1934 private members bill that suggested a quota:

[B]ased on the number of registered electors of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, other than those of the City of London and the universities, divided by six hundred and fifty.3

This bill did not get far, but the 1944 Speaker's Conference (which led to the modern system of regular reviews) recommended that:

Redistribution shall be effected on the basis of qualified electorate.4

The standard Unit of electorate for each Member of the House of Commons for Great Britain shall be a quota ascertained by divided the total electorate in Great Britain by the total number of seats in Great Britain.5

This shift does not seem to have been a point of principle, but more reflected that the distance between the two concepts had closed. The franchise had been expanded to all women in 1928 and the only people who were not the ‘electorate' were children and non-citizens. In 1910, 29.5% of the population over 21 had the right to vote, by 1939 it was 98.5%.6 Excluding children, population and electorate can be used almost interchangeably.

Given the conceptual difference was very small, there was also a practical benefit to using the electoral registers. The war had meant that there was no census in 1941 and there was no recent data to draw from to estimate the population in each constituency. Switching to electors gave a number to understand the number of electors in each area, as well as an apparent improvement in precision.

Non-citizens were a smaller group than would be understood today. The right to vote has never been tied to being a citizen of the UK, but at first being a British subject and later a Commonwealth citizen (with equivalent rights maintained for citizens of Ireland after the republic was established).7 The large scale migration in the second half of the twentieth century mostly came from vote-eligible Commonwealth countries. These groups aside, the population contained very few ‘foreign' people until relatively recently.

The percentage of the population born in what the census historically understood as ‘foreign' places increased slowly. In 1911, only 0.8% of the population was ‘foreign' born as opposed to being a ‘British Subject' (born in the UK or elsewhere).8 By the 1971 census 8% of the population were born abroad, but only 2% were born outside the Commonwealth/Ireland.9 By 2001, this had only increased to 4%. These numbers are still too high for determining the population of eligible voters because they count the foreign born as opposed to their nationality.10 For 2001 both sets of numbers are available and the number of people who were ‘foreign' born and who had not become British citizens was only 2%. Up to the end of the twentieth century, very few adults living in the UK did not have voting rights.

Migration from the EU in the last few decades has changed this picture. From 2000 to 2018, the proportion of people living in the UK with non-Commonwealth/Irish citizenships rose from 2% to 6% of the population.11 Many of this group may be happy remaining a citizen of their home country and not naturalising (or expect to return to their home country later in life) but this remains a significant democratic anomaly. Over 1 in 20 adults living in the UK are not part of the electorate and many EU immigrants are concentrated in specific areas rather than evenly distributed throughout the country.12 As of the 2011 census of England and Wales, 50% of ineligible adults lived in only 81 (14%) of constituencies. The nine seats (1.5%) with the highest numbers contain 11% of all ineligible adults. An issue that was a marginal democratic issue in the 1940s has become more significant, with an impact on electoral results.

Citizens vs registered voters

The ineligible population is a new democratic problem but is less significant in impact than the longer running problem of under-registration of the eligible population, where many people who are eligible to vote are not registered to vote. This would not be a problem if under-registration was uniform across society, but the under-representation is uneven. Certain groups of eligible voters are systematically under-registered, and these groups are not distributed equally geographically.

The processes that update the register are not equally effective for all groups. The Electoral Commission's report on the 2018 register found that one of the largest drivers of under-registration was frequency of moving home. While people become more likely to be registered the longer they live at an address, groups like private renters are moving much more and so are having the clock constantly reset. This means that as a group, private renters are 58% complete on the register compared to 86% for those owning a house with a mortgage. Groups in society that are less likely to own are in turn less likely to be registered.

Different ethnic groups have different rates of registration. People with a white ethnic background have an 84% registration rate, but those with an Asian or Black ethnic background were registered at a rate of around 75%. There is a clear intersection with the renting issue, with a Runnymede Trust finding that "black and minority ethnic households and recent migrants are more likely to be living in the private rented sector"13. There is also interaction with different citizenships, UK and Irish nationals were registered at 86%, while Commonwealth nationals were registered at a rate of 62%. A 1998 survey found a number of reasons given by ethnic minority respondents for not being registered:

As far as the reasons for non-registration are concerned, some respondents mentioned the doubt about their residence status. Other reasons included the language difficulty and the fear of racial harassment and racial attacks from extreme right-wing groups who could identify Chinese, South Asians and others from their names on the electoral register.14

A lack of awareness that non-British Commonwealth citizens are eligible to vote is likely to be a factor, but the perceived risks of registration are worth noting. Regardless of the exact factors in each case, some citizens face higher barriers to registration than others.

This under-representation has an effect on the creation of constituency boundaries. In principle any eligible person can register in the run-up to an election, but if a group is less present on the register when it is used to create electoral boundaries their parliamentary representation is reduced in any outcome. Geographic areas where under-representation factors are especially prominent will then be assigned less seats. One example of this is that less seats end up assigned to London than might otherwise be the case. Equalising the number of registered voters means that some MPs end up representing not just more people, but more vote-eligible citizens than others. Groups of citizens who need greater effect to be consistently registered than others are squeezed into fewer constituencies than those who the system registers easily.

One approach to this is to fix the under-registration issue, but another would be to disconnect from the registration data altogether. The Electoral Reform Society recommend the return to census data to create boundaries based on eligible voters:

The next boundary review should be based on a more accurate and complete data source than the electoral register, to ensure all citizens are counted. We recommend using census population statistics, complemented by citizenship information provided by passport data.

In a report for the Constitution Society, Lewis Baston similarly argues the census should be used and more explicitly tasked to find accurate numbers of potential electors in an area:

An alternative, and much more stable and reliable, basis for drawing the basis for parliamentary constituencies is fortunately available in the decennial Census, by far the best and most complete record of the UK population available. Internationally it is more common to use population, rather than registered electorate, as the base number for allocating seats. While this would mean a break from the past pattern of allocating seats in the UK, a middle option is available in the form of using the data from the Census to arrive at a number for each nation, region, local authority and ward of people entitled through age and nationality to appear on the electoral register.

As the census happens only once a decade, this would be twice as frequent as the current status quo, and only marginally slower than the new plans to hold a review every eight years. These alternate approaches are a different way of achieving the same democratic principle of giving constituencies equal numbers of potential voters, but would also a knock-on effect on the election results.

The effect on previous elections

The previous section has shown that different measures of counting might lead to different outcomes, but how different would these be? This section simulates the effect of drawing boundaries using the three options explored.

Attempts to model the effects of boundary reviews typically take the new boundaries and use patterns of local election results to try and estimate how the composition of voters has changed. In this case, there is no alternate set of boundaries to test, just different principles that might lead to a number of different sets of boundaries being drawn.

If just trying to understand the theoretical effect of different principles, a less complicated method can be used to examine different metrics: weighted seats. This approach involves revaluing seats compared to the fraction of the electorate (or the population) they contain. The relative value of seats (and MPs) changes depending if they are currently under- or over-represented, but their composition does not. The same party wins in each seat but the weight given to those seats changes, and with that the overall power of a party in Parliament. We can examine the rough direction of different schemes of representation without developing different maps for each approach.

This is exploring a theoretical question but weighting seats is a valid practical approach to the underlying problem. Equalisation by moving boundaries around the population is complicated and has to be done more frequently the tighter the requirements. In contrast, equalising voters by giving MPs different voting weights is a simpler operation and can be done very close to the election with up to date numbers. Jurij Topleck and Ashira Ostrow have argued that this might provide a better way of reaching legal ‘one person one vote' requirements in the US, and it is especially relevant when some boundaries cannot be moved because of geographic or political constraints. In the US context this allows better equalisation within the context of immovable state lines, but in the UK would solve the issue of various island constituencies being hard to integrate with mainland constituencies, or allow geographically smaller constituencies in areas like the sparsely populated Highlands.

The results of this process are not predictions of what would actually have happened if the boundaries for recent elections had been drawn differently. Moving boundaries rather than weights changes the composition of seats (which might change winners) and the numbers used to create boundaries would not be as up to date in the election year as in the below simulations. What it does allow is an understanding of the likely direction and scale of change when comparing different principles.

2019 electorate vs 2019 population

Taking the 2019 election results, Table 1 shows what the results would have been if voting weight had been equalising by 2019 electoral register or 2019 population.15

| Party | Actual | Register weighted | Population weighted |

|---|---|---|---|

Conservative | 365 | 372.2 | 359.2 |

Labour | 202 | 199.3 | 213.4 |

Scottish National Party | 48 | 45.7 | 43.9 |

Liberal Democrat | 11 | 10.3 | 10.3 |

Democratic Unionist Party | 8 | 7.9 | 8.2 |

Sinn Fein | 7 | 6.9 | 7.3 |

Plaid Cymru | 4 | 2.7 | 2.6 |

Social Democratic and Labour Party | 2 | 2 | 2.1 |

Alliance | 1 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

Speaker | 1 | 1.1 | 1 |

Green | 1 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

Table 1. Shares in the 2019 election by different weighting

This shows that equalising on registered electors gives a small increase (seven units) in the weight of Conservative seats, while the Labour party has an 11 unit increase if the seats are weighted by population.

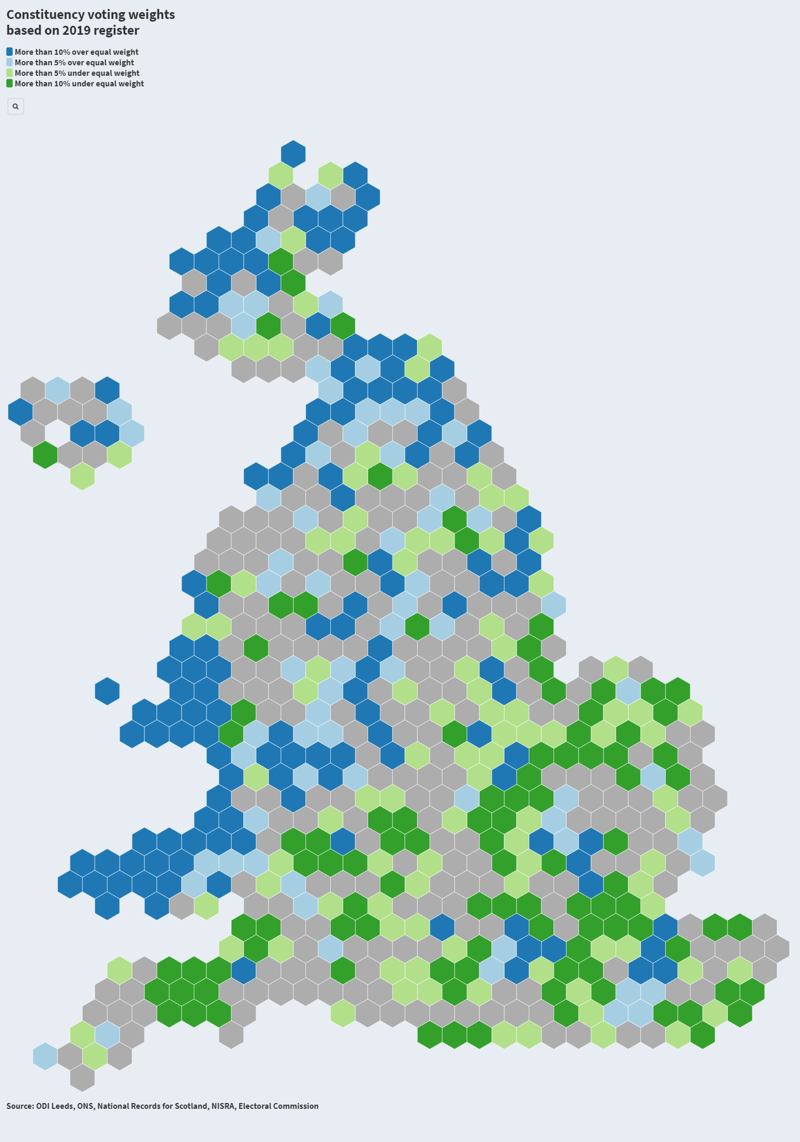

Importantly, even if seats stay roughly the same between parties, there will be a geographical redistribution of seats (broadly speaking in all scenarios, flowing south and east). The current geographical over and under weighting compared to using the 2019 electoral register can be seen in chart 1. As a similar exercise found, the effect of reallocating seats by population increases the relative weight of urban constituencies (especially in London and Birmingham).16 The specific conclusion in that study is that enfrancising immigrants would likely lead to political parties in aggregate (if not necessarily individually) to adopt more pro-immigrant positions. The more general point is that redrawing the map may affect the internal composition of parties in a way that changes policies, even without any new voters.

Chart 1 - Constituency voting weights based on 2019 register.Explore on Flourish.

Electoral register and population over time

The same general pattern holds in the 2015 and 2017 elections. Table 2 shows the difference between the status quo and weighting on the electoral register in the last few elections for the four largest parties This shows that this weighting on the electoral register is consistently to the Conservative party's advantage. Running the same analysis with population data (Table 3) shows the reverse and Labour benefits from the redistribution. In both cases part of the benefit comes from reducing the slight over-representation of Scotland in the current boundaries (and in the 2015 and 2019 election, this is mostly a problem for the SNP).

| Party | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

Conservative | 9.3 | 10.5 | 7.2 |

Labour | -5.8 | -5.6 | -2.7 |

Scottish National Party | -0.9 | -2.3 | -2.3 |

Liberal Democrat | -1.1 | -0.7 | -0.7 |

Table 2. Difference between the actual result and the weighted register result in recent election years.

| Party | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

Conservative | 0.7 | -2.1 | -5.8 |

Labour | 5.8 | 7 | 11.4 |

Scottish National Party | -4.6 | -3.2 | -4.1 |

Liberal Democrat | -1.4 | -0.9 | -0.7 |

Table 3. Difference between the actual result and the weighted population result in recent election years.

Estimating the electorate

Turning to estimates of eligible voters not based on the register, there are no easily available estimates for recent election years. The different annual mid-year predictions for constituencies in individual nations make it easy to count adults, but there is not a complete or recent estimate of how many of those adults are eligible to vote. Using the proportion of vote-eligible adults by constituency in the 2011 census for England and Wales the adult population figures were adjusted downwards by each constituency, with constituencies in Scotland and Northern Ireland adjusted downwards by the average percentage for that nation.

Table 4 explores the change if you shift from the status quo to weighting on the number of eligible voters. This shows that while based on the same principle (equalising electors) as equalising on the electoral register, the difference between the weighted result and the current results is much smaller. In 2019, it only increases the Conservative Party weighting by 1 unit as opposed to 7. This suggests that equalising on registered voters rather than estimates of eligible voters inflates Conservative seats at the expense of Labour. Exactly the same principle implemented in different ways can have a different impact.

| Party | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

Conservative | 5.8 | 4.1 | 1.2 |

Labour | -0.8 | -0.2 | 3.1 |

Scottish National Party | -3.1 | -2 | -2.6 |

Liberal Democrat | -1.1 | -0.9 | -0.8 |

Table 4. Difference between the actual result and the weighted estimated electorate result in recent election years.

Forms of representation

Given different ways of equalising the electorate have predictable political effects, is there any reason to prefer one over another that is unrelated to their effect on outcomes? A potential way to examine this is to see electorate versus population as a debate not about how constituencies should be measured, but about rival ideas of representation. Should voters be ‘equal' when they go to the ballot box, or should constituents across the country have an equal share in their MP? Both schools of thought have emerged in discussions around apportionment, but are rarely taken to their logical conclusions.

Equal shares of a representative

One reason to equalise the population of constituencies would be that it is already the case that MPs represent the entire population, they are just not given equal resources to do so. In the 1944 debate on the bill that set up the modern system of reapportionment, Herbert Morrison described the key principle as being that "[S]o far as it is practicable each Member ought to represent an equal number of constituents." This does not suggest equality at an election, but an equal number of constituents. The current equalisation of electors is not necessarily the original intent: the concern and language at the time seems to have been with creating equality of constituents.

The distinction between the electorate-based approach and population-based was less clear in the past. By 1969, a speech by Michael Winstanley (Liberal) shows that both understandings are present but not the idea that there might be a conflict between them:

I drew attention to three reasons why I thought it was desirable for the House to aim at broadly equal Parliamentary constituencies: first, to share the load amongst members of the House as equitably as possible; secondly, to provide, so far as possible, roughly equal access to a Member of Parliament by constituents; and, thirdly, the more important matter of the fundamental principle of, not only one man, one vote, but one vote, one value.

Here ideas of equality of voters and equality of constituents are different, but fundamentally in alignment rather than opposition. But this also raises the question of exactly what is meant by the term ‘constituent', and if it is consistent across time.

Unhelpfully, the term ‘constituent' is used inconsistently to refer to both voters and residents, but this seems to have always been the case rather than the result of a shift. The origins of the word ‘constituent' relate to someone appointing someone else as an agent or representative but currently the official parliament website defines a constituent as "the name given to every person who lives within or is eligible to vote in a constituency". Similarly, the Oxford English Dictionary allows "a voting member or an an inhabitant of a constituency", and an edition from the 1930s also shows this understanding would have been present in the 1940s debate referenced above:

One of those who elect another to a public office, esp. as their representative in a legislative assembly ; an elector; more widely, any inhabitant of the district or place so represented.

This leans towards the expansive definition of constituent. However, a reason for caution is the ambiguity in this area makes it unclear if all MPs would understand their job as representing non-citizens.

There are different schools of thought among MPs about what their job is, and a great amount of flexibility to indulge this disagreement. As Sarah Childs points out, MPs dislike defining their role too much. The MP code of conduct has several mentions of constituents but does not define exactly what a constituent is. The glossary on the website cannot necessarily be seen as reflective of what all MPs believe. That many MPs deal with immigration related queries (and that there is advice provided for them to do so), suggests that in general MPs do constituency service for non-citizens and understand them as ‘constituents' when they do so. However, this remains a fuzzy point, with slips that suggest words are not being used with clear and universal meanings. For instance, Mark Harper (Conservative) in a 2011 debate talked of the importance of equalising a ‘constituent's vote':

That is because we want the weight of a constituent's vote to be equal across the United Kingdom, and that is an important principle.

This suggests that some MPs may understand constituents when used in this kind of debate as meaning those who are eligible to vote. That said, Harper has separately used the term to refer to residents:

The job of Ian Blackford is to represent the people who live in his constituency, as I represent those who live in mine, not to represent the spaces in his constituency. It is the people who matter.

Generally, ‘constituents' seems not to be a term with a fixed meaning and is used by MPs to refer to several slightly different groups of people they may represent.

Similar confusion appears in discussions between non-voting but eligible residents and and ineligible residents. A debate in 2010 shows MPs making the same point about slightly different groups:

Thornberry (Labour): Is not the most important point, and the one to which coalition Members are not listening, that constituencies may well be much more equal than local registration figures show? In constituencies such as my right hon. Friend's and mine where there is very high churn, there are a large number of Europeans, and people who want to be on the register but cannot. A large number of people simply do not count, but they do exist and are a valuable part of our constituencies.

Ruddock (Labour): I agree absolutely. I repeat that those are real people contributing to our communities and living among us, and we ought to value them. They may not be on the electoral register, but they certainly exist. The hon. Member for Epping Forest agreed that as Members of Parliament, we have to treat unregistered people equally with those who are registered if they come through our doors. That is a most important principle. We need to recognise their existence, value them and be willing to count them in as people who could be registered, even if they are not.

Williams (Liberal Democrat): Nobody would disagree with the right hon. Lady that we must make every effort to register everybody who is eligible, but does she not agree that there are two different issues to consider? One is that every Member of Parliament should be elected by an equal number of electors, and the other is that if one Member has to represent more people than others do, perhaps more resources should be made available to them. She is confusing two issues.

Ruddock (Labour): I am not at all. I am talking about the equal worth of people who are eligible to be registered but are not, and those who are registered. That is the difference between our position and the Government's.

The confusion here is that there are several different arguments happening at once. Ruddock is talking about the unfairness of shrinking constituencies because of eligible but not registered voters. Thornberry is mostly making this point, but also in referencing the Europeans in her seat is making a broader point about the existence of non-voting residents. Some MPs (like Thornberry) have constituencies with a large proportion of non-eligible voters (17% in 2011), but will have the same resources as those that do not. If boundaries have been drawn to equalise the electorate, this represents an unfairness to all in that constituency because they have a lesser share in a representative than is the case elsewhere. But does this require equality of representation or, as Roger Williams suggests, additional budget for caseworkers? If MPs are just providing a service, do constituents need equal representation, or equal resources?

Seeing the problem as one that can be resolved by additional case workers raises a key issue with this interpretation of an MP's role: why should we bother with elections if hiring more staff solves issues of representation? The idea of an MP as a service provider hides the fact it is foremost a political role. Changing the criteria to balance on population would not only have an impact on service provision, but on political balance. This is a concern because while an MP may be able to intercede on behalf of a constituent, there is no guarantee their political actions are in that constituent's interest if they had no say in selecting them.

Representation without participation

Including and counting those who cannot vote may seem more inclusive but is not always to the benefit of those non-voters. For instance, the US has very clear historical reasons for apportioning based on population. Political representation in the early republic was defined by an argument about if the southern states could count enslaved people as part of the population for the purpose of having more seats in the House of Representatives, or if only free people should be counted. The resulting compromise of counting a slave as three-fifths of a person is often read as an injustice to those enslaved, but slave owners would have preferred it if they were recognised as full (but unfree) persons. The slave states gained political power as a result of the presence of slaves who would have no say in the exercise of that power.

Long after the abolishment of slavery, Jim Crow laws that restricted voting continued to allow white supremacist politicians to benefit from the additional representation the presence of African-Americans provided, while denying substantive representation to that group. As current systems of mass incarceration in the US can be seen as a transformation of older systems of racial oppression, this same mechanism continues to function through the location of prisons. US prison populations represent a highly concentrated group of people, unable to vote, yet counted as living in the physical location of the prison. This results in a system of prison gerrymandering, where the location of prisons is a political prize. The location of a prison inflates the relative influence of an area without increasing the number of voters. This has a political effect because it is often a transformation of urban voters into rural non-voters, reducing the size of seats more likely to elect Democrats and growing those more likely to elect Republicans:

Because prisons are disproportionately built in rural areas but most incarcerated people call urban areas home, counting prisoners in the wrong place results in a systematic transfer of population and political clout from urban to rural areas. 60% of Illinois' prisoners are from Cook County (Chicago), yet 99% of them are counted outside the county.

A reason to be suspicious of equalisation based on population is that it is changing representation based on the presence of a person without the input of that person. Without enfrancising people, it cannot be said whether counting them for the purposes of apportionment is to their benefit or not.17

Political representation

Several quotes in previous sections have shown the belief of MPs that they have a duty to represent more than the people who voted for them. As Joan Ruddock (Labour) put it in 2010, "as Members of Parliament we serve all our constituents and all our constituencies." But should we accept this? Leaving aside intention, is it practically possible for MPs to provide the same service to all constituents? There may be any number of interventions an MP can perform impartially for any constituent but in other cases their political projects may be to the advantage of some constituents and the disadvantage of others.

In the 1944 debate on the redistribution of parliamentary seats, Godfrey Nicholson (Conservative) and Robert Young (Labour) had an exchange that gets into the difference being represented and being politically represented:

Nicholson: The hon. Lady the Member for Anglesey (Miss Lloyd George) kept on saying how monstrous it was that the Conservatives in Durham or the Labour people in the Home Counties should not be represented, and that the Members for those places do not regard themselves as representing these people. If the hon. Lady's father wrote asking for my help in any matter, I should help him as conscientiously as I should help a Conservative. Let us not forget that we are not delegates, but representatives. I represent my whole constituency, men, women and children.

Young: I do not think the hon. Gentleman has met the position. I represent my constituency in the sense that if anybody sends a grievance to me I attend to it, but I do not represent my political opponents. This is a political House and I am sent here on a political basis. I do not presume to represent the Conservatives in my constituency in relation to their political opinions, and I do not suppose that any member sitting on that side can represent my views.

Nicholson: That would be very difficult.

Young: Very difficult, I agree. It may be impossible for some of them. It is all nonsense to talk about our being representative of the whole constituency in a political sense.

The context of this debate is a complaint that the bill did not create a system of proportional representation and regardless of if votes were equally distributed, outcomes were not.

Nicholson argues against the need for proportional representation as he can represent everyone regardless of their views, but Young argues that MPs cannot claim to represent the politics of constituents they oppose. Your MP may be willing to be your representative and advocate for apolitical problems, but fundamentally cannot represent your politics if they do not share them. As an MP put it in 1834:

A certain correspondence ought to exist between the opinions of Members and their constituents. A man could not be a real representative of any body of electors if he differed materially from them on important points; in such an event he ought to withdraw, and find another constituency.

In practice, there are many MPs with a weak correspondence between their opinions and their constituents. After the 2019 election, the average MP had 46% of voters opposing them, with 229 MPs (35%) not reaching 50% support. Those MPs in particular cannot claim in any substantial terms to be politically representative of their community. This is an improvement on the results in 2015, where the average voter did not vote for their MP but this improvement may just be a result of voters adapting to the system. As a YouGov poll found 32% voted tactically in 2019, and assuming a fraction of these ended up voting for the winner, the number of people without their preferred representation is still likely to be higher than 50%.

Equality of outcomes

If the problem with equalising based on population is that it means people have numerical representation but not political representation, it is also a problem if this happens under electorate equalisation. As Lord Lippey commented during the debates on the 2011 Act, the implications of wanting equal votes logically go beyond equalising constituencies:

[I]t is believed-we have heard this from other Ministers as well-that this Bill creates votes of equal weight. It is possible to have a system in which all votes have equal weight. It is called PR [proportional representation] and most of us are against it.

While the motivation for having equal numbers of electors in each seat is "making sure that every vote counts the same", taking this seriously goes into areas the Conservative Party is generally opposed to: electoral systems that deliver results proportional to the votes cast.

One problem in this area is we lack clear ways to talk about the different kinds of problems that can mean people's votes do not count equally. Jonathan Still suggested a set of criteria for political equality, which I have simplified:

- It doesn't matter who you are, your vote should count the same (Suffrage)

- It doesn't matter where you are, your vote should count the same (Equal shares)

- It doesn't matter which party/candidate you vote for, your vote should count the same (Independence)

- Everyone should have the representation they want (Proportional representation)

In the debate in the UK, most complaints revolve around the idea of equal shares and that the number of voters has too much variation between constituencies. However, the largest influence on the outcome of UK elections is violations of the independence principle. The impact of your vote changes depending how other people in your constituency have voted.

The efficiency of how voters are distributed leads to some political opinions being better represented than others. For instance, the Conservative Party complains that its constituencies are larger than others, but in general their vote is distributed in such a way that gives them more seats than their ‘fair share'. Voters who are more tightly clustered are more able to secure representation, unless they are too-tightly clustered, in which case they are wasted. This can be expressed as distorting the value of individual votes as well as unfairness to parties.

Still uses the concept of anonymity to explain this problem, arguing that in a system where there is equality voters should be able to swap their preferences without affecting the result. If swapping votes between equal-sized constituencies can change the result, the value of a vote is changing depending on where it is cast. This is the same type of problem as that posed by unequal constituencies: all votes are counted the same, but they do not have the same impact because of the structure of the election.

The distinction between numerical representation and political representation also becomes clearer through this lens. The first demands equal representation, the second that voters get not only representation, but the representation they voted for. Arguments that it is important to fulfill equal shares are concerned with providing an equality of numerical representation, whereas arguments for a more complete political equality are arguing for an equality of political representation.

When arguing against PR for local elections, Ranil Jayawardena (Conservative) stressed the importance of clear constituency representation and quotes Edmund Burke on the importance of a representative exercising their own judgement as they should be representatives rather than delegates. This is an example of how conceptions of an MPs role form in reaction to demands that politics should be different. If an MP's job is to use their own judgement, it is no longer a problem that they have political disagreements with a majority of their constituents.

As it happens, the general public is much keener than MPs on the idea that MPs should be delegates rather than ‘representatives' (63% of the public versus 20% of MPs), but the distinction between the two forms becomes a lot less important if people simply have the representation they prefer. The argument that political representatives can represent people they campaigned against as effectively as people who support them is a justification of current outcomes, and is not credible in its own right.

Political arguments

As part of the announced 2020 changes, the need for boundary plans to be confirmed by a parliamentary vote is set to be removed. Chloe Smith (Minister for the Constitution and Devolution) argued that this helps reject the "accusation that, despite the fact that the organisations that conduct the reviews are rightly independent, boundary reform could be politicised". As shown in 1969, 2013 and 2018, being able to delay or not implement the boundary changes is a way political power is exerted in the process. But the more significant way the boundary reviews are politicised is that parliamentary majorities write the rules that the boundary commissions then independently execute. Parties advocate different sets of rules (and the principles that justify them) on the basis of how these rules might indirectly benefit them.

Letting elected politicians draw their own boundaries is obviously open to abuse, but moving this to an independent body while leaving the rules a matter of political debate just moves the problem upstream. There are alternate structures that might introduce more of a disconnect (for instance, referring decisions on the underlying rules of politics to citizens assemblies and referendums) but truly depoliticising electoral and boundary reform just is not possible because different systems are likely to lead to different outcomes, and people are aware of that when they decide between them.

When trying to map out arguments about electoral and political structures, the key question is how seriously you should take what people are saying. Many arguments about electoral processes are in reality about electoral outcomes. You can propose alternate ways of resolving the problems, but this is unimportant if the idea of which problems are important is derived retrospectively from the desired ‘solution'.

Conclusion

The arguments about boundary reform represent a lot of time, attention and money being spent on what is in the grand scheme of things, a relatively minor issue for the equality of voters. Entabled in those arguments is the question of exactly who MPs exist to represent, and if this should change with the presence of a larger number of non-voting residents.

Within the idea of equalising constituencies, there are several different possible methods, and different principles can be used to justify each one. If the goal is equality of access to representation, there is a good case that constituencies should be equalised on population, but also that this should be viewed suspiciously as including non-eligible voters can change political outcomes without their input.

If alternatively the goal is equality of voters in an election, there is a case to equalise based on the electorate. But this should also be seen as suspicious if it is not accompanied by measures to address the more substantial issues that cause inequality between voters.

Taking the arguments presented for boundary reform in earnest, the importance of making every vote count the same leads you towards ideas of proportional representation. If you reject that, the arguments and ideas about an MPs role made in opposition to proportional representation support the idea of equalising based on population.

In reality, we end up with a debate about a relatively minor issue of political equality, because addressing the main issue threatens the ability of the main parties to create majority governments. There may be reasonable arguments for prioritising other aspects of a political system over political equality, but it is a problem when language of equality is used to disguise what is fundamentally a debate over political power.

The next reapportionment will equalise based on the electoral register and be justified on the grounds of fairness and ‘making votes count the same'. Given the broader issues of voter equality, as well as the known problems of under-registration of specific groups and places, there is no reason to accept any reapportionment based on the electoral register as inherently representing greater fairness to voters. An approach based on the eligible voters identified by the 2021 census might achieve the same goal better but this does not provide a firm approach to the underlying cause of the shift: an notable proportion of adult residents who are eligible to vote.

One possibility would be to recognise that the de facto policy through the second half of the twentieth century was that most non-citizens with residency rights had voting rights. Given this extensive right already granted, it could be extended to cover all non-UK citizens with the right to be resident in the UK. This ideally would be in a broader framework of reciprocal rights between countries, but the UK has previously extended rights without the reverse being guaranteed. Acting unilaterally solves an immediate democratic problem at home, while making the case that British citizens abroad should similarly be able to have influence over the polity they live and work in.

Moving the population and the electorate closer to harmony simplifies many questions of representation, both in making the census easily usable for boundary changes and in addressing the issue of a small number of MPs having a much larger number of residents than others, without the additional resources to represent them. The democratic problem caused by non-eligible residents has a simple solution: let them vote.

Notes

1:Rossiter, D.J., R.J. Johnston, and C. J. Pattie, The Boundary Commissions: Redrawing the UK's Map of Parliamentary Constituencies (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999), p 40

2:Rossiter, D.J., R.J. Johnston, and C. J. Pattie, The Boundary Commissions: Redrawing the UK's Map of Parliamentary Constituencies (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999), p 53

3:Rossiter, D.J., R.J. Johnston, and C. J. Pattie, The Boundary Commissions: Redrawing the UK's Map of Parliamentary Constituencies (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999), p 64

4:Speaker's letter to Prime Minister, p. 370

5:Rossiter, D.J., R.J. Johnston, and C. J. Pattie, The Boundary Commissions: Redrawing the UK's Map of Parliamentary Constituencies (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999), p 72

6:Rossiter, D.J., R.J. Johnston, and C. J. Pattie, The Boundary Commissions: Redrawing the UK's Map of Parliamentary Constituencies (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999), p 62

7:The British state had maintained that the residents of the Free State were British subjects, which was of course contested in Ireland.

9:Registrar General for England and Wales ; General Register Office Scotland (2002): 1971 Census aggregate data. UK Data Service. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5257/census/aggregate-1971-1

10:The shift in what census summaries see as important and unimportant information is interesting in terms of changing understandings of how the UK relates to the world. Commonwealth vs elsewhere divisions become less highlighted as immigration rights were limited, while modern ONS summaries of nationality are mostly concerned with the EU.

11:Based on this ONS series, assuming all people with nationalities not in the top 60 were citizens of non-commonwealth nations.

12:Migrants in the UK: An Overview - Migration Observatory

13:Megan McFarlane (2014), Ethnicity, health and the private rented sector

14:Anwar, M. (2010). The participation of ethnic minorities in British politics. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27(3), 533–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/136918301200266220, pp. 535-536

15:Extending from the previous ONS mid-year estimates to 2019, but the result is effectively the same if you use 2018 numbers.

16:Fox, S., Johnston, R. and Manley, D. (2016), If Immigrants Could Vote in the UK: A Thought Experiment with Data from the 2015 General Election. The Political Quarterly, 87: 500-508. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.12309

17:Denying the franchise to felons similarly has an effect on boundaries if counting only the electorate, but under population counts they in effect lose two votes - both their own they cannot exercise and that the location of their body is used to increase the total in other areas.